/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/33151225/90000873.0.jpg)

Sixty years ago today, the Supreme Court struck down the "separate but equal" doctrine in Brown v. Board of Education, ending legal segregation in American schools. It was a historic decision that some now fear is being undermined as schools once again divide by race. Here's a broader look at some ways that race and educational opportunity have intersected over the past 60 years — and where racial inequity persists today.

The Brown decision really did desegregate schools

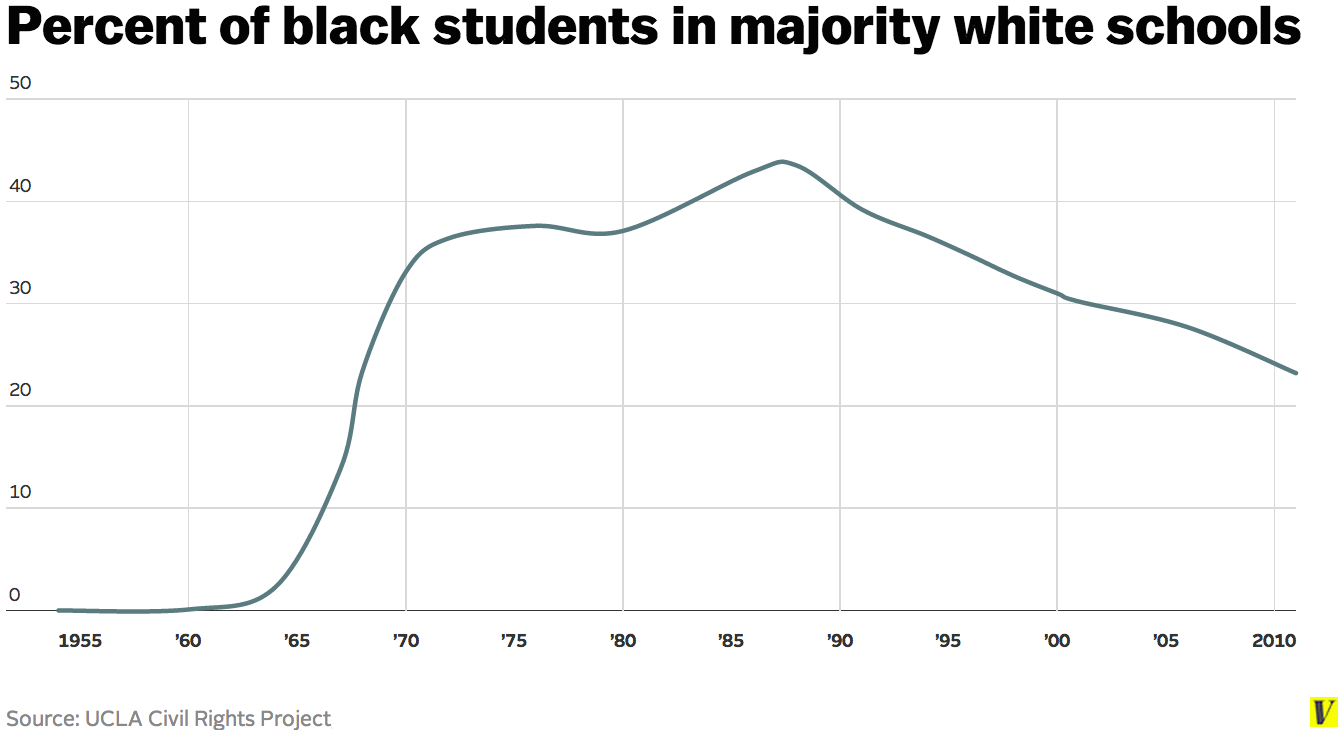

Progress was slow in the immediate aftermath of the Brown decision. Southern whites found ways to perpetuate segregation — opening low-tuition private "academies" that shut out black students in response to desegregation orders, for example. Outside the South, protests — violent ones — ensued over busing and other policies meant to ensure racial balance in schools. Still, in the formerly legally segregated southern schools that were the most affected by the Brown decision, desegregation made real progress. In 1988, the peak of school integration, close to half of black students attended majority-white schools.

Then a series of Supreme Court decisions narrowed the scope of desegregation orders, the federal government backed off on its enforcement, and schools once again became separated by race. By 2011, just 23 percent of black students were in majority-white schools, the Civil Rights Project at the University of California-Los Angeles found — the same proportion as in 1968. And it's now the Northeast, not the South, that is the most intensely segregated.

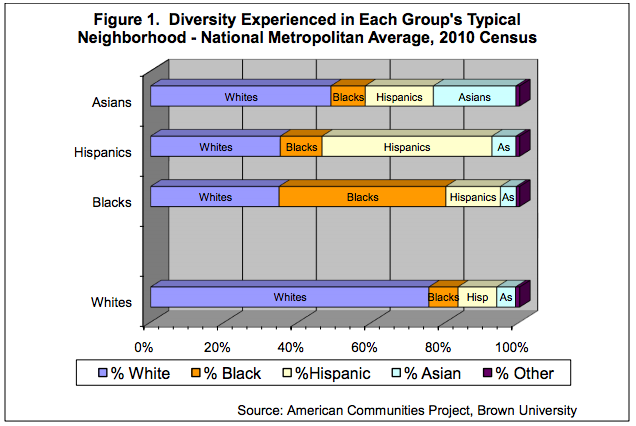

Residential segregation has long governed school segregation

"White flight" from urban school districts in the post-Brown era just moved inequality for black and white students to the district level; instead of separate and unequal schools, there were separate and unequal districts, suburban and urban, with different amounts of property tax revenue.

When federal courts began easing up on desegregation orders at the direction of the Supreme Court, longstanding patterns of housing segregation meant that schools quickly resegregated. Wonkblog's Emily Badger has a long look at the interplay between housing policy and school segregation, including the fact that, by age group, school-age kids live in more segregated environments than anyone else.

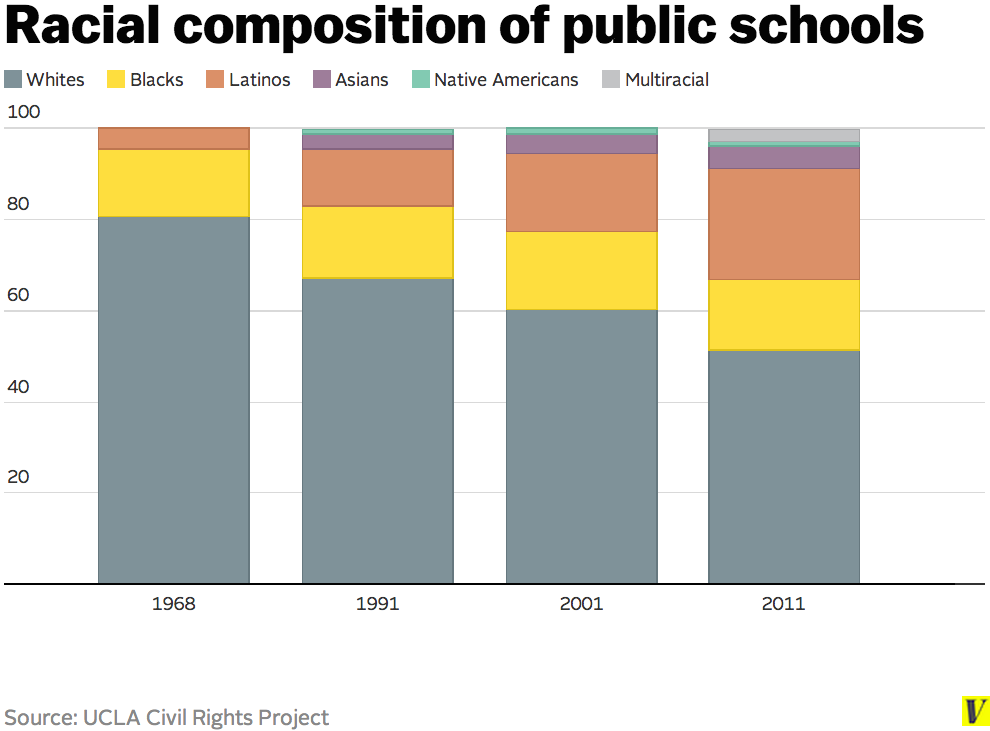

The demographics of schoolkids have changed

In 1965, the first year the Civil Rights Project at the University of California-Los Angeles has data on school segregation, about 4 in 5 kids in public school were white. Now white students are on the cusp of becoming a minority within the public schools.

From generation to generation, whites make up a shrinking percentage of all Americans. And children enrolled in the public schools are less likely to be white than their generation as a whole. According to the Brookings Institution's analysis of Census data, 55 percent of 5- to 17-year-old Americans are white; just 51 percent of public school students are.

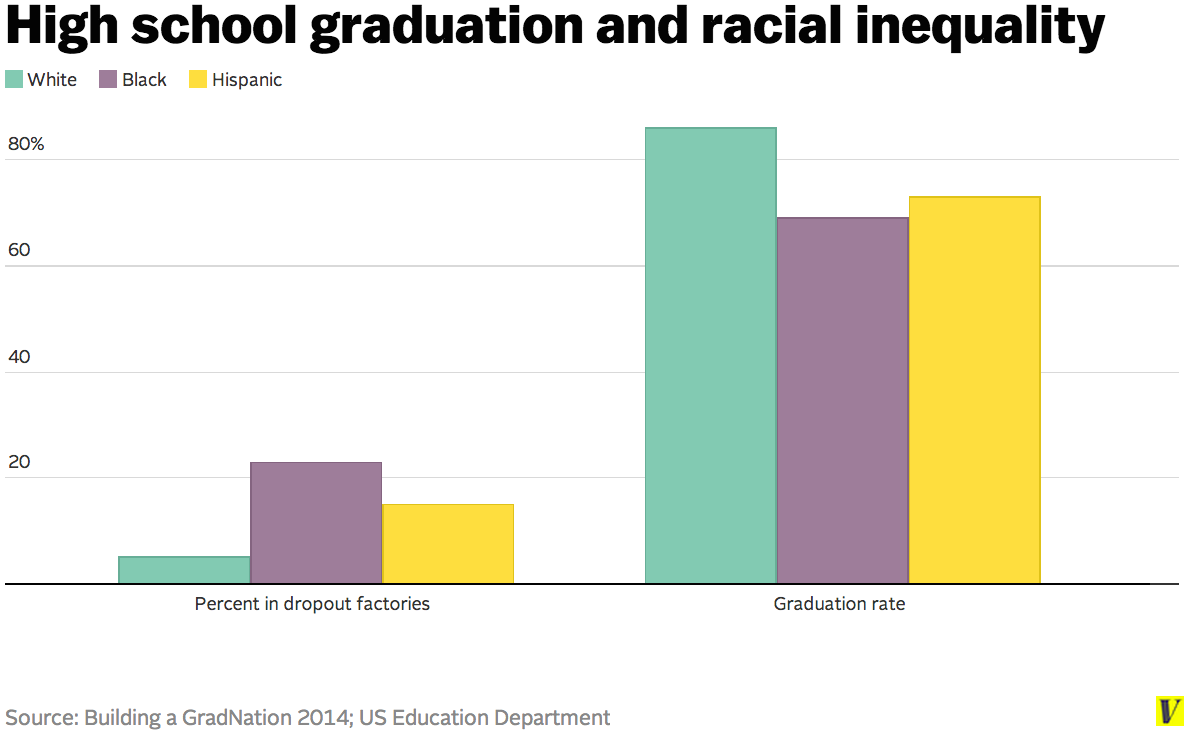

Minority students are more likely to attend low-performing schools

White and Asian students attend schools that, on average, perform around the 60th percentile on state tests, while black students attend schools that perform at around the 35th percentile and Hispanic students are at schools performing at the 40th, according to the US2010 project at Brown University.

"Dropout factory" high schools — where less than 60 percent of students who start as freshmen end up graduating — are disappearing. Still, where those schools remain, students of color are disproportionately clustered: 23 percent of black students and 15 percent of Hispanic students attend dropout factories for high school, compared to 5 percent of white students.

Still, that's a tremendous improvement over a decade ago, when nearly half of black students and 40 percent of Hispanic students were in dropout factories, compared to 11 percent of white students.

The graduation rate for black and Hispanic students also lags behind their white peers. Nationally, 69 percent of black students graduate from high school, compared to 86 percent of white students; 73 percent of Hispanic students and 67 percent of American Indian students graduate.

Inequalities in K-12 education are carried over into higher education and to the next generation

First, some seemingly good news: College enrollment rates are roughly comparable for black and white high school graduates. Hispanic college enrollment rates doubled between 1995 and 2009; black enrollment rates grew 73 percent.

But the college experiences of whites look very different from their minority peers, the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce found. White college enrollments grew more modestly in the same time period, but their enrollment growth went overwhelmingly to the 468 most selective four-year colleges. Black and Hispanic students' enrollment growth was driven by the rest — two- and four-year colleges without admissions criteria.

Different colleges have vastly different levels of resources: The 468 most selective colleges spend more than twice as much educating each student as the nonselective colleges do. And students at the selective colleges are more likely to graduate than students at open-access institutions — even if the two groups had equally promising high school transcripts. Students with lower test scores who attended the most selective colleges are more likely to graduate than students with higher test scores who attended unselective colleges.

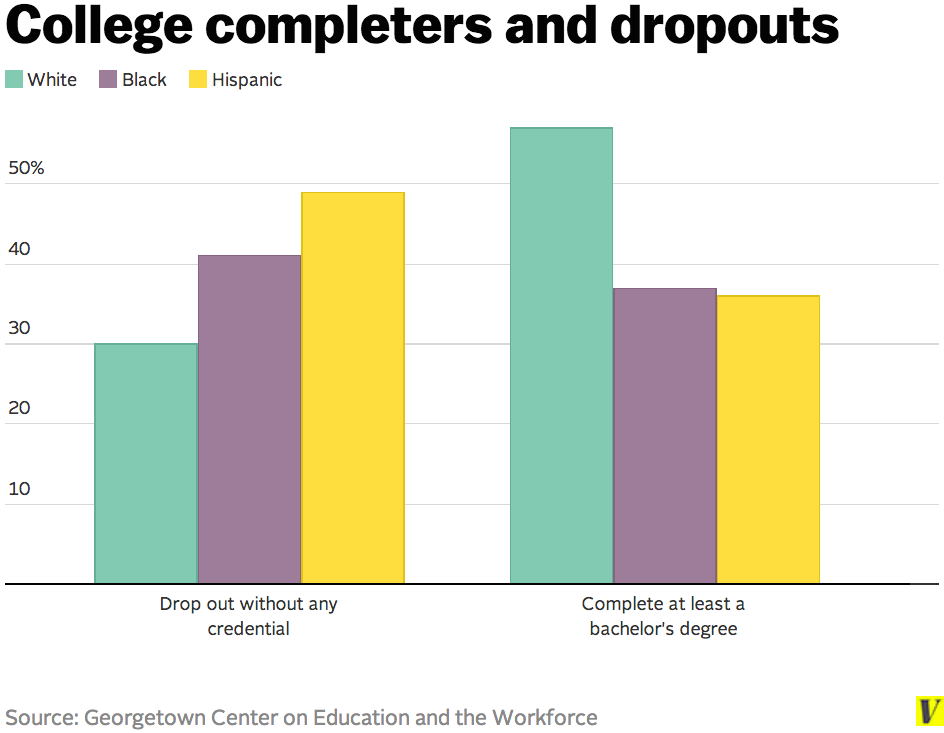

By age 30, whites are almost twice as likely to have completed a bachelor's degree as African-Americans, and and three times as likely as Hispanics.

This matters not just for them, but for their children, because parents' education levels strongly predict how educated their children will be. The "separate and unequal" education system, the researchers concluded, "reinforces the intergenerational reproduction of white racial privilege."