"My College Dream" is a series of first-person essays by college students about their college and career aspirations, the serious money struggles they faced along the way and the real-world consequences that resulted from their circumstances — and their decisions. They will publish every Monday for the next few weeks on CNBC.

It started out as a simple assignment: Write an essay about money.

Journalism students at three universities were asked by SABEW, a professional organization of business journalists, to write about their experiences with money. Those essays would, in turn, be published on the SABEW website as a way to put the students' writing in front of SABEW members, which include active writers, editors and producers from major news organizations. The students would be paid $100 for their time through a sponsorship from the National Endowment for Financial Education (NEFE).

The assignment turned up some themes you might expect, such as getting creative when you run out of money, saving for spring break and applying for financial aid. But something else emerged: Many students were facing serious financial crises.

"We were expecting to hear about students' experiences handling money in college," said Kathleen Graham, the executive director of SABEW. "We were surprised by some of the heartfelt compelling stories about students in financial crisis with their families going bankrupt, making tough decisions about spending money on food or other essential living items and even experiencing devastating health issues that impacted their financial situations."

Having to choose: Go to class or go to work

For example, one student said she often had to choose: Go to class, or go to work so she could pay the bills?

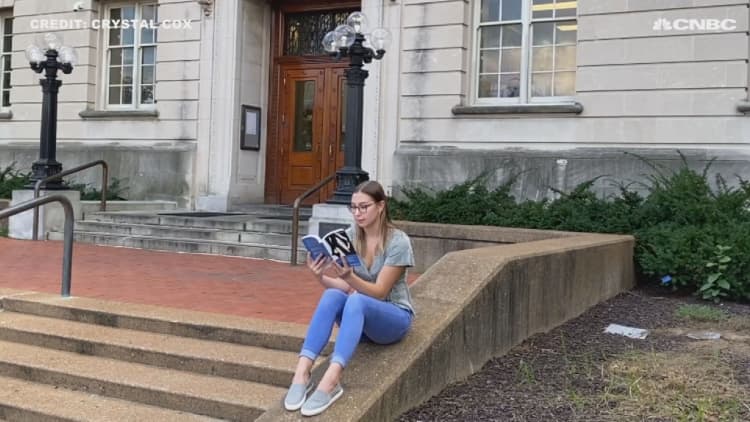

"In my first two years at college, I've had to make a decision that my high school self could not have imagined: Go to class or be able to afford to eat," says Crystal Cox, now a junior at the University of Missouri. "This is the reality that I, and many students who come from low-income families, face."

Cox says she thinks it's tougher for low-income students because they can't afford to work unpaid internships. And she hopes that her professors understand when she has to miss class so she can go to work.

"There's an erroneous belief that the younger generation is lazy and entitled, but I don't think that people understand the amount of pressure we're under," Cox says. "We are overworked and underpaid while trying to better our lives, or even just to make ends meet. I would love for universities and employers to recognize our hard work and meet us halfway so that we can achieve our dreams."

Cox isn't alone. Eight out of 10 college students work while they're in school — and the number of hours they're working is on the rise, according to Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce analysis of data from the National Center on Education. Nearly half (45%) work at least 30 hours a week, and 25% work full-time while going to school full-time.

"Working while learning takes a greater toll on low-income students," says Anthony P. Carnevale, director and research professor at the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. "There are about 6 million working learners who are also low income, and they are disproportionately women, blacks and Latinos."

Carnevale says 59% of low-income students who work 15 hours or more had a C average or lower. Working that many hours can take a toll on their emotional and physical well-being. It can also have a ripple effect on their academic career — and their future. They typically don't have time to get internships related to their field, which when combined with a low GPA affects their ability to compete for jobs when they get out of school, especially in a tight labor market.

Other students faced unexpected developments on the family front — their parents were going through a divorce, losing their family home to foreclosure, losing their jobs or unexpectedly pulling their financial support for the student's education. In some cases it was a health issue — like a student who battled cancer before even moving into his dorm room, shaping the rest of his college and career trajectory.

CNBC's My College Dream series:

This college student had to choose: Go to class, or go to work so she can afford to eat

Think college is hard? This student tackled cancer before he even moved into his dorm room

How this college student's responsible money decision took a turn and forced her to drop out

This college student's family has been in financial crisis for nearly seven years

The statistics are staggering: Annual tuition at four-year public colleges has soared 37% since 2008, and in some states it's more than 60%, according to the College Board. What's more, since 1980, tuition and fees at four-year public colleges and universities have risen 19 times faster than median family income, according to the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce.

And, of course, in that time, the financial crisis hit, putting an additional strain on families. Parents lost their jobs, and families lost their homes.

Parents aren't talking to their kids about money

Martha Steffens, the SABEW chair in business and financial journalism at the University of Missouri — SABEW stands for Society of Advancing Business Editing and Writing — oversees the essays students from Missouri write for this program. She said the recession hit students really hard — and highlighted a major problem: A lot of parents aren't talking to their kids about money, especially when times are tough.

"One student told me how heartbreaking it was that their parents lied to them about losing their jobs during the Great Recession. I actually had multiple students say their parents hid that from them when they were younger," Steffens said. "It seems parents and children don't have a good relationship about money. They shield their kids from these harsh realities, and it creates a disconnect."

Steffens says she thinks that disconnect has broader implications: Parents aren't preparing their kids for reality. Kids set their sights on their "dream" school and whether or not they or their family can afford it, the parents don't want to burst that bubble.

Kids pick out their dream school and often a safety school. Steffens says. "But absent from that conversation is 'This is my affordable school.'"

"I think that's a quintessential part of being American: Not wanting to limit horizons," Steffens says. "I think that plays into how students wind up with college debt."

Some students learned the hard way the consequences of their decisions, like Alexandria Montoya. Going to Arizona State was a dream for her. And, thanks to a $50,000 scholarship, a full-time job as a waitress (while going to school full-time) and help from her dad, she was doing it! Then, she fell behind on her tuition. So, after three semesters, she made what seemed like a responsible money decision at the time: She took a semester off to pay it back. She took on a second job, working seven days a week — determined to get back on track. She finally paid off her tuition and went back to school for her junior year and thought she was back on track. But it turns out, that wasn't the case.

"They informed me that I had lost the scholarship because I never filled out a deferment form. And, they said I owed ASU $15,000 for that semester and wouldn't be able to return until I paid it back. So, I dropped out … again," said Montoya, who completed two years at Arizona State University but isn't sure when she'll be able to return.

Less than 60 percent of students who start at a four-year school complete their degree within six years, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. That number drops below 40 percent when you're looking at two-year community colleges. What's more, those dropouts are likely to still have a mound of student debt – even without the diploma.

Montoya isn't giving up on her dream — but she might modify it. She's currently thinking that maybe she should consider a less expensive school and perhaps even change her major from journalism to something in the service industry. Not restaurant management, but more the corporate level.

"I want to finish school. And I'm halfway there — four semesters in," Montoya says. "But it doesn't have to be from a popular or higher college. I think I can just get a degree."

Rich or poor — no one is immune to money problems

The essay by Noelle Schon is an illustration that money problems, like cancer, don't care if you're young or old, rich or poor. She grew up in a family that was financially well off, and her parents set up a college fund so her education would be paid for. But then Noelle's parents split up when she was a teenager and she says her family spent the next seven years in a state of financial crisis while her parents sorted it out. They moved four times and her father lost his job.

Then, just as her mom was getting them financially back on track, a sick grandparent came to live with them. Noelle learned much sooner than other students how important money and a good economy are for the future — and that you have to prepare for what happens if both of those things fall apart. Now a junior at Arizona State University, Noelle says she's learned a lot from how her mom has navigated the family's financial crisis. But she's also considering changing her major to something more conducive to her family's new reality. Something that would allow her more time at home to take a turn helping to care for her grandmother.

SABEW has agreed to let CNBC publish updated versions of the students' essays. And, updated is an understatement – several of these students' lives and career paths changed dramatically in a few months since the publish of their first essay. While the initial vision for the SABEW project was to connect students with professionals in the media, we decided to call this series "My College Dream" because when we spoke to the students, every story seemed to begin with "My college dream was …." and then they would talk about the serious money struggles they faced along the way and the real-world consequences that resulted from their circumstances – and their decisions. Their paths and plans changed and for some, their dreams now seem like they may never come true.

"I had no idea taking a semester off would affect my entire life," Montoya says. "I just hope that other students can look at my story and maybe learn from it and make their lives as college students be a little bit easier."

CNBC connected each student with a financial advisor to offer them some advice and answer questions to help them get back on a solid financial path.

One thing that emerged from these discussions is that a lot of the money lessons kids learn – or don't learn – tend to come from their parents. That was especially pronounced with the kids who came from low-income backgrounds.

Montoya says she always jokes to friends, "I grew up living paycheck to paycheck – I'm going to die living paycheck to paycheck."

Cathy Curtis, the financial advisor she was paired with and the founder of Curtis Financial Planning, said it doesn't have to be that way.

"You don't have to continue that family tradition! You can break it."

Stacy Francis, the president and CEO of Francis Financial who was paired with Crystal Cox, says one of her first pieces of advice – even if you don't have a lot or make a lot — is to make a budget. You may think it seems like a no-brainer but Francis says you'd be surprised — when you have to write down what you spend, you tend to spend less.

Do your own math

It's also important to choose your career wisely — and do the math.

Francis says she's met people who've gotten master's degrees and even gone as far as a PhD in say non-profit management. Then they graduate with $120,000 in loans. They start out making $48,000 a year.

"They find themselves in a situation where they can't even make the minimum payments on their loans and are questioning that hard work that they did," Francis says.

That is something we heard time and time again from these students: They're working so hard – and yet, it still isn't enough.

The issue is deeply personal for Francis – she changed her major to finance when she learned that her grandmother stayed in an abusive marriage because she didn't know enough about money. One day, she asked her grandmother why she stayed. Her grandmother said she believed there was no other choice — she didn't have the financial stability to change her life. From then on, Francis was determined to not only remain on a solid financial path herself — but to help other women who feel powerless because of financial instability.

So first — and this may be hard for some — you need to research how much entry-level jobs in your field pay. And, you should calculate how much your average student loan payment will be when it comes time to pay back your loans, Francis says. Don't just bank on your dream job, assuming the math will pan out. Don't wait until you feel stuck.

Of course, you want a career that makes you happy. If you're not a hospital person, you can rule out being a doctor or nurse. But, Francis says, you also need to figure out what type of job you need to live in a financially safe position.

"You want to make sure that you make a decision that leads you to have a solid happy career," Francis said.

The essays in CNBC's "My College Dream" series were originally published on the SABEW.org website as part of their College Connect series, sponsored by the National Endowment for Financial Education. They will publish on Mondays for the next four weeks on CNBC.

Cindy Perman is the partnerships editor at CNBC and a governor on the board of SABEW.

Disclosure: NBCUniversal and Comcast Ventures are investors in Acorns.