You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Can you name 50 U.S. colleges or universities that (i) don’t carry the name of a state and (ii) don’t have a Division I football or basketball team? If you can, you’re an elite reader of Inside Higher Ed. If not, you’re probably suffering from myopia like the rest of us.

Myopia in higher education is the tendency to mistake elite institutions -- the Harvard of Love Story (or really the Harvard of any of Kevin Carey’s favorite films) -- for the whole of our wonderful, diverse system. But this is not the only form of myopia afflicting our sector.

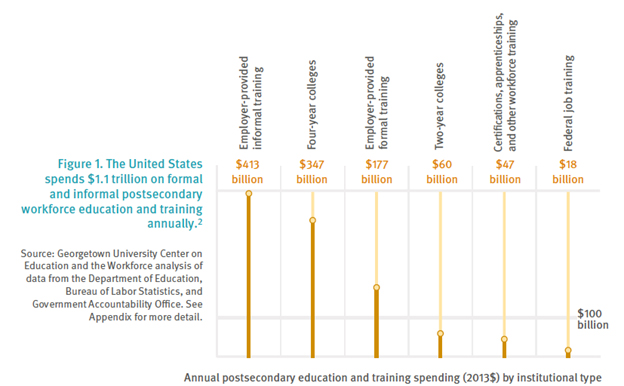

Conventional wisdom on postsecondary education says that the entire enterprise is indistinguishable from the work of colleges and universities. However, a recent report by Tony Carnevale and the Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce serves as a corrective lens: colleges and universities represent $407 billion of the $1.1 trillion spent on postsecondary education and training, or only 37 percent of the total.

On the other hand, spending on training provided by employers is nearly 50 percent greater than all college and university spending. And broken down by age group, while colleges and universities dominate total postsecondary spending for young adults, they account for less than a quarter of total spending on adult education and training.

|

Ages |

College and University Share of Total Spending on Postsecondary Education |

|

18-24 |

78% |

|

25+ |

23% |

It appears as if higher education is suffering from double myopia: the first misconception of the system is mistaking elite universities for all colleges and universities. The second is mistaking colleges and universities for all postsecondary education.

As we refocus our vision, the next big opportunity for growth in education may not be in attempting to “do college better,” but rather found in the yawning gap between what we typically conceive as postsecondary education and the world of work.

***

U.S. employers are developing a global reputation for wanting the perfectly qualified candidate delivered on a silver spoon -- or they won’t hire. As Peter Capelli of Penn’s Wharton School astutely notes, “Employers are demanding more of job candidates than ever before. They want prospective workers to be able to fill a role right away, without any training or ramp-up time. To get a job, you have to have that job already.”

He calls it the “Home Depot view of the hiring process,” where filling a job vacancy is “akin to replacing a part in a washing machine.” The store either has the part, or it doesn’t. And if it doesn’t, the employer waits. The result is that while there are over eight million unemployed workers, we have over five million unfilled jobs, and perhaps as many articles featuring employers whining about unprepared workers.

In his wonderful monograph “Why Good People Can’t Get Jobs,” Capelli says we have a “skills standoff,” with employers dissatisfied with the level of new hire preparation but unwilling to provide training or otherwise engage in skill-building activities with candidates. One major reason? Employers don’t want to risk investing in employees who may leave the company soon after.

And so the supposed skills gap is a byproduct of a trust gap. How can we get employers to trust new hires and engage in training and skill building? Likewise, how can we get candidates to invest in their own skill building -- perhaps even skill building specific to an employer -- so that employers find the “right part in a washing machine”?

***

Bridging the skills gap is not work that employers are prepared to do. In response, over the past several years we have seen a variety of intermediaries emerging at the intersection of higher education and the labor market in an area we call pre-hire training.

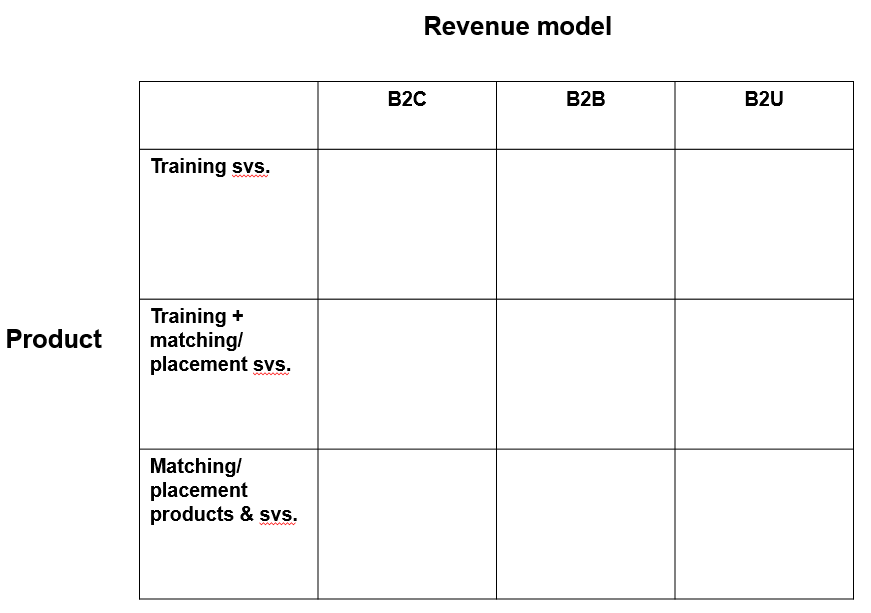

Some focus solely on training. Some focus on training and placement or matching services. Others focus solely on matching candidates with employers. In terms of revenue, some seek revenue from job seekers. Others generate revenue from employers. Still others attempt to charge education providers. The result is a matrix that looks something like this:

While these pre-hire training companies are diverse and include boot camps, online training providers, employment brokers, staffing companies, e-portfolio providers, and competency and credentials marketplaces, what they have in common is the following:

- Pre-hire training is skill specific and often employer specific.

- Employers are not asked or expected to bear the cost of pre-hire training, or engage in any way until candidates are trained. Rather, the cost of pre-hire training is borne by the candidate or the intermediary. (Even when the intermediary bears the cost of the training, the candidate hasn’t been hired yet, so the employee has skin in the game.)

- Once intermediaries are successful in aggregating a pipeline of qualified candidates for employers, employers jump in with both feet and are willing to compensate intermediaries for producing employees who will be productive from day one as well as engage in developing and improving training curricula.

Fast-growing pre-hire training intermediaries like Galvanize, eIntern, Credly, ProSky and Portfolium are establishing structures and programs that encourage employers and candidates to trust one another. For example, pre-hire training companies that are confident in their ability to train and place candidates, and thereby attract employers, can guarantee some outcome to candidates to bring them in the door in the first instance. This could be a guaranteed interview, or even a job guarantee if they successfully complete the pre-hire training.

***

While some of this should be the province of colleges and universities, much of it won’t be. Higher education institutions should be in the business of equipping students with general skills like coding or reading a balance sheet -- tangible skills that are directly relevant to thousands of workplaces across the country.

However, I don’t see colleges and universities involved in matching students with employers at the level of the competency -- a proposition that requires institutions to assess students’ competencies and then match, rather than simply arranging job fairs and interviews. Nor do I see institutions engaging in employer-specific training on products, systems and process, so new hires can hit the ground running like an experienced employee. When we get beyond skills-based training to matching students with employers, intermediaries aggregating candidates from multiple institutions and providing matching and training services for multiple employers will be much more productive for students and employers than a single institution: scale matters.

Many institutions (and their students) will benefit from partnerships with these intermediaries. By connecting students with employers, students will have a better sense of the placement and salary outcomes from their program of study. But colleges and universities need to be prepared for the consequences: higher ROI programs will benefit at the expense of low ROI programs; shorter, less expensive programs with credentials that clearly convey competencies are likely to flourish.

The impact of this new generation of pre-hire training companies on students and employers is likely to be more profound. They will provide employers with visibility into a deep pool of future talent, along with the means to engage and attract this talent. And they will provide students with a much clearer road map of the education and training required in order to be considered by employers of choice. While our vision now is still quite cloudy, pre-hire training companies have the potential to restore it to 20/20, and dramatically improve the efficiency of our labor and postsecondary education markets.