Recession, Recovery & Robotics: Can CTE and Reno’s Reinvented Schools Avert a COVID Classroom Crisis?

How going all in on career and technical education after the last economic downturn could now help the city weather the pandemic’s K-shaped recession

By Beth Hawkins | August 6, 2021

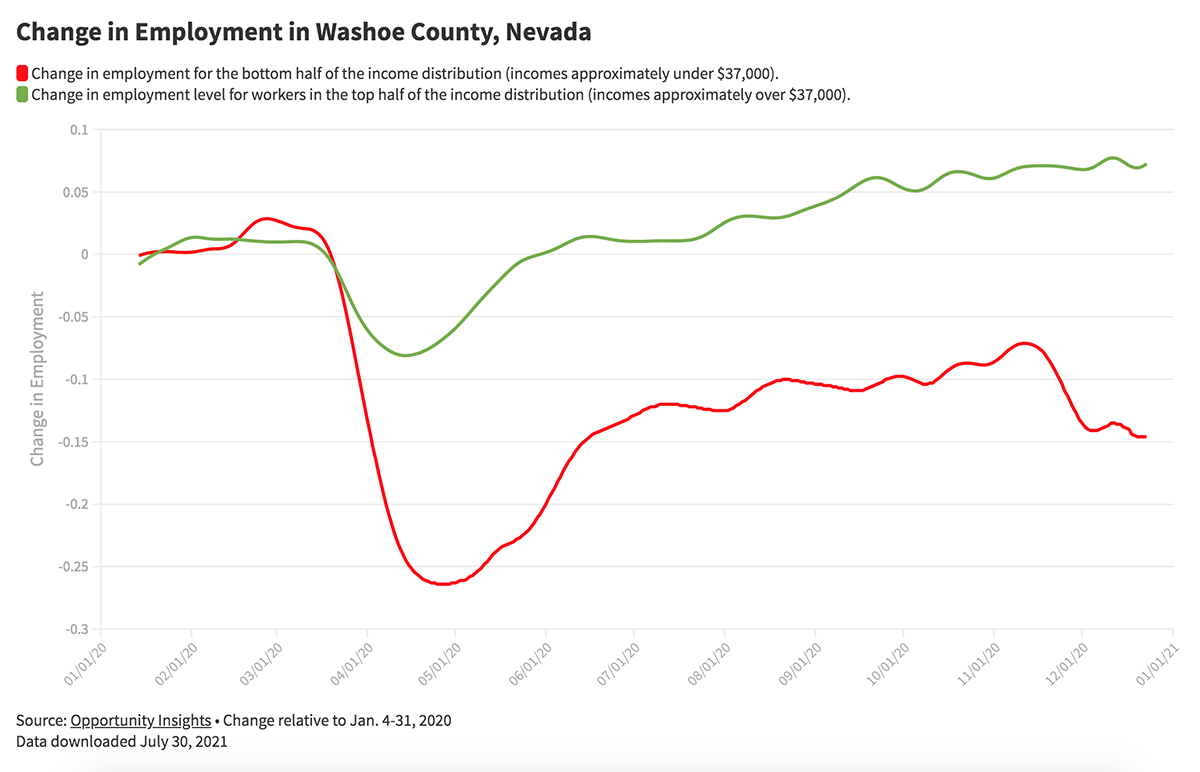

On Nov. 28, 2020, the COVID-19 infection rate in Washoe County, Nevada, crested at 113 new cases per 100,000 residents. What that grim statistic meant to residents of Reno, Tahoe and the county’s other small cities depended greatly on their socioeconomic status.

Employment on that day, for instance, was down 1 percent over January 2020 — low, but also deceptive. Employment among middle-income workers, those making $27,000 to $60,000 a year, was flat.

But among those making less than $27,000, it fell 22 percent. Meanwhile, for residents earning more than the area’s median income, employment actually rose an astonishing 19 percent.

That disparity is a glaring illustration of the so-called K-shaped economic recovery — one of the features of the pandemic recession that most troubles economists.

Past economic slumps have had more of a V-shape: an across-the-board dip followed by a relatively uniform and quick return to pre-recession conditions.

This time is different. For many high earners, those at the top of the K, COVID’s roiling effect on the economy was a blip. They may be working remotely, but they’re working. They are not, however, spending money the way they did before COVID-19, on restaurant meals, growlers, travel, mani-pedis, Uber rides — services their lower-income neighbors provide as they eke out a living.

The week that Reno’s case count peaked, small-business revenue in the area was down as much as 31 percent. But overall, consumer spending dropped as little as 8 percent. The money was still flowing — just not to the folks at the bottom of the K.

It’s a problem nationwide, and likely to worsen in coming years, because many of the low-wage jobs lost since the start of the pandemic won’t be replaced, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Jobs that will require a college or graduate degree, such as health care and technology occupations, are expected to grow. But those requiring a high school diploma or less — chief among them the restaurant, hotel and customer service jobs whose workers who have long been the spine of Reno’s economy — will continue to contract. Early indicators show COVID has accelerated this shift, which has broad implications for K-12 education.

When the pandemic recession struck, economists John Friedman and Raj Chetty realized it looked different from previous downturns. While even small changes in the way money changes hands create ripples, COVID was a shockwave. Co-founders of Opportunity Insights — a team at Harvard University that researches income inequality and education’s potential to lift children out of poverty — they persuaded credit card companies, payroll processors and other businesses that track money as it moves through the economy in real time to turn over what are essentially trade secrets. Using that information, the researchers built a nationwide online pandemic tracker capable of providing a down-to-the-day snapshot of who is spending and who is struggling, by income level, city, state and county and, in some instances, by zip code.

The data quickly revealed stunning implications on virtually every front.

In Reno, as in many places, affluent residents at the top of the recession’s K shape bounced back right away — much more quickly than in a typical downturn. But their new spending patterns crippled the businesses that supported their lower-income neighbors; those impoverished families on the bottom continue to struggle disproportionately on every front, beset by challenges long proven to be detrimental to children’s ability to learn in school.

Researchers, Friedman told The 74, fear the resulting losses — of jobs, of loved ones to COVID, of mental health supports and reliable food supplies — may have even more devastating impacts for children that schools were already failing to serve, with education’s potential for lifting a family out of poverty moving further out of reach.

(Friedman and Chetty update the tracker as the underlying information changes. The data in this story was downloaded June 29, 2021.)

The Opportunity Insights tracker contains one academic dataset: student participation and progress on the math app Zearn, which one-fourth of the nation’s K-5 students have access to. Immediately after schools closed, use of the app among low-income students “completely dropped off,” notes Zearn CEO Shalinee Sharma. As they started logging on again, a yawning gap became apparent. A year into the pandemic, these students’ progress was behind where it should have been, while their wealthier peers were ahead 28 percent.

WATCH: Beth Hawkins details her latest investigation into COVID’s K-shaped recession and how the fallout will challenge America’s schools

New studies by McKinsey & Co. and the nonprofit assessment concern NWEA found wide disparities between white/affluent students and their low-income peers/children of color. Depending on grade and subject, low-income students ended the 2020-21 school year with up to seven months of unfinished learning.

In many ways, because Reno’s economic development officials took steps after the Great Recession to address major shifts in the economy, the city is better positioned than most places to weather COVID’s economic shocks. In particular, the community’s leaders tapped the local school district to help train the workforce needed to fuel a clean energy hub, with its thousands of good jobs.

The resulting ripples from that prescient decision are being felt as early as kindergarten.

Gambling and quickie divorces

When Tesla announced it was to break ground in 2014 on a much-anticipated Gigafactory, where it would develop a new class of batteries that could free consumers from fossil fuels, the headlines wrote themselves.

“Reno, Nevada, may have just won one of the most coveted economic prizes in America,” declared the San Francisco Chronicle’s “Fossils & Photons” blog.

“Tesla Motors’ $5 billion Gigafactory may be the best thing to happen to northern Nevada since the silver rush of the 1850s,” gushed a Bloomberg piece.

The $1.2 billion state incentive package that sealed the deal was a “bold gamble” on lessening Nevada’s dependence on casinos, according to the magazine Area Development Site and Facility Planning.

The anticipated jackpot — $100 billion in economic growth over the next two decades — “keeps supercharging Reno,” quipped the news site Teslarati.

The city, the stories noted, beat out glitzier locations because of its easy freeway and rail access to Tesla’s flagship Bay Area facilities, its lack of corporate income taxes and even its status as the jumping-off spot for the futuristic desert festival Burning Man. The pundits weren’t kidding about this last selling point: Like lots of Silicon Valley technocrati, Tesla founder Elon Musk himself is a “Burner” — a moniker analysts explained earnestly in auto industry publications.

But in the same breath where they mentioned the good jobs the tech boom would create, the pundits decried the poor state of Nevada’s education systems. The deal the state and Musk eventually arrived at would require that half the jobs under Tesla’s control — 6,500 permanent positions and thousands more to build the Gigafactory — be filled by Nevada residents. But the state’s schools were not graduating students with the necessary skills.

Nevada has the smallest higher education system in the nation, with a correspondingly low rate of postsecondary enrollment. Last year, Nevada students posted the nation’s lowest average score on the ACT college entrance exam, at 17.9. On the most recent National Assessment of Educational Progress, often referred to as the nation’s report card, Nevada students outperformed only their peers in Louisiana, New Mexico, Alaska and Washington, D.C.

Historically, state leaders felt little urgency to confront the problem. An economy centered on gambling and quickie divorces put no pressure on public education institutions at any level to graduate students with skills beyond those needed to work in the gaming and hospitality industries.

“There was … a demand side to the problem,” Elliot Parker, then the head of the Department of Economics at the University of Nevada, Reno, wrote in the journal Nevada Review in the wake of the Great Recession of 2008. “Since before the crash, many young people without a degree could earn above-average wages working in casinos or construction, at least for a while.”

For 50 years, a near-monopoly on legal gambling helped the state weather economic swings. Even after the number of Native American casinos began to rise elsewhere, Las Vegas continued to appeal to tourists. But not Reno.

In 2000, Californians voted to allow tribal casinos to offer slot machines and card games, paving the way for them to build resorts. No longer was there a compelling reason for northern Californians, Reno’s chief visitors, to make the trip across the state line. The region’s gambling revenue fell by two-thirds, a big drop at any time but especially hard to overcome once the Great Recession struck in 2008. Unemployment soared to 14 percent in 2010 — the worst in the country. By 2011, home values had fallen by 58 percent, leaving 70 percent of mortgage holders underwater and devastating construction, until then the metro area’s other major source of jobs.

In 2012, then-Gov. Brian Sandoval released a plan for diversifying the state’s economy. He proposed investments in higher education but said that wouldn’t be enough. Apprenticeships and other programs to provide job skills certification to students not necessarily seeking a college degree would be an important part of broadening the state’s employment base.

To that end, he asked the state’s underperforming K-12 schools to work with regional economic development agencies to bolster career and technical education, or CTE, and make sure the training programs actually taught the skills needed by the employers that regional officials were trying to entice.

As an example of the kind of strategy needed, Sandoval singled out Washoe County Public Schools’ Signature Academies, then a relatively new initiative to offer four-year high school programs with specific career focuses. Students who choose one of the themed courses of study can earn college credit and industry-approved job credentials in fields such as agriculture, engineering, information technology and health sciences.

In creating CTE programs, districts and states face several pitfalls, says Anthony Carnevale, director of the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. The first is ensuring that offerings both engage students and are aligned to employers’ needs — an effort that is now required under the federal Carl D. Perkins Act. Programs that achieve this, he says, are relatively rare. The second is avoiding the biased tracking of generations past, when schools placed disproportionate numbers of economically disadvantaged students and youth of color in vocational training programs to prepare them for low-wage jobs, rather than advanced academics that led to higher education.

In Washoe County Public Schools, the district that includes Reno, mandatory federal reporting by race and gender shows that boys make up 52 percent of enrollment and 56 percent of CTE participants. Some 44 percent of students are white, as are 48 percent of program participants, while Latino students are 37 percent of CTE enrollment and 43 percent of the overall student body.

The district offers 36 CTE programs in 12 high schools, falling into six broad groupings: agriculture and natural resources; information technology and media; health science and public safety; business and marketing; education, hospitality and human services; and skilled and technical sciences. In many of the programs, seniors have the opportunity to earn an industry certification or other job credential, or complete an internship. Nearly one-fourth of 2020 12th-graders — 1,229 graduates — finished the three or more years of study in a particular field needed to be considered a “CTE completer.”

Washoe’s arts and communications programs are still its most popular CTE tracks, with more than 1,500 students participating in the 2019-20 school year. Information technology is a close second. While the number of students enrolled in traditional career programs such as education and hospitality remains high, interest in more cutting-edge offerings is growing. Programs geared toward the region’s economic development efforts include manufacturing, with 800 participants; transportation and logistics, with 575; science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) with 550, and 900 in health sciences.

High school offerings are planned using economic development data that in most states guides decisions about whom public colleges and universities should train, and for what jobs. The Economic Development Agency of Western Nevada provides the district with weekly reports on job openings, the wages those jobs are likely to pay and which fields are poised to grow or shrink.

The nearly 8,000 students in Washoe’s CTE programs can study clean energy technologies like wind, solar, geothermal and hydropower, automation, greenhouse management, environmental engineering, manufacturing and, of course, automotive technology. Opened in 2002, the Academy of Arts, Careers and Technologies is entirely career-focused and enrolls students from anywhere in the county. A second all-CTE high school is scheduled to open in fall 2023.

Before the pandemic, two-thirds of district elementary schools had robotics clubs, with offerings ranging from simple computer coding games to First Lego League and First Robotics, a competition in which students have a short time to build an industrial-size robot that will compete against other teams in a field game.

Incorporating economic forecasting into school planning has been a game-changer, says Josh Hartzog, the director of the department in charge of the programs: “Where do our schools need to be positioned 10, 20, 30 years from now, given that we have no idea what the economy will look like?”

Equipping today’s students with career credentials is terrific, he says. But the real key to future prosperity is to make sure they graduate with skills like critical-thinking, problem-solving, entrepreneurial drive and ability to refine ideas that will increase the odds they will create their own high-tech innovation or start their own businesses.

The robotics club effect

As the Gigafactory began to rise from the desert, Tesla founder Musk was vocal about whom he wanted working in it. A track record of “exceptional achievement” was his chief qualification. “There’s no need even to have a college degree at all, or even high school,” Musk — a college dropout himself — told the German publication Auto Bild. “If somebody graduated from a great university, that may be an indication that they will be capable of great things, but it’s not necessarily the case.”

Still under construction, the plant may, at 10 million square feet, eventually be the world’s largest building. Right now, the facility is about 30 percent complete, with the remainder to be designed around innovations gleaned from the work taking place inside now. Musk hopes his exceptional achievers can conjure the Holy Grail of clean, renewable energy: batteries that are greener, cheaper, smaller and capable of powering everything from cell phones to cars to homes.

When Tesla’s first electric cars were introduced in 2008, their price tags — often six figures — put them out of reach of most customers. One reason the cars were so expensive was the cost of producing the lithium-ion batteries they run on. If the company could reduce the cost of the batteries by 30 percent by bringing research and production under one roof, Tesla could produce cars for middle-class drivers. Indeed, the first $35,000 Model 3 rolled off the assembly line in 2017.

The batteries are cheaper, but inside the Gigafactory, the quest for better ones not reliant on cobalt — expensive and problematic to mine — continues, with the first production lines running around the clock. A host of high-tech employers including Google, Apple, Panasonic and Intuit have set up shop in the Gigafactory’s shadow, hoping to capitalize on similar innovations and creating fierce competition for skilled labor.

The feedback loop created by the new employers, the region’s economic development officials and the K-12 school system could be a positive departure from past CTE practices, which too often result in re-creating the low-skill vo-tech programming of the post-World War II era, says Carnevale.

“Employer involvement is great, but it’s kind of like love,” he says. “Everyone wants it and there is never enough. They’re very fickle. They don’t work for you.”

One reason he’s optimistic about Washoe’s programs is that instead of focusing on job training per se, the partnership is capitalizing on hands-on experiences to motivate students to develop the traits and intellectual abilities that will ensure they leave high school ready for college or a skilled career.

As part of its agreement with the state, Tesla agreed to spend $37.5 million on K-12 education. As people started working in the Gigafactory, the company analyzed the performance evaluations of its most effective workers. What it found was that many had participated in robotics clubs as kids.

Reno is awash in robots, says Amy Fleming, until recently the economic development agency’s director of workforce development and now with the Governor’s Office of Workforce Innovation. Visitors to Tesla’s campus encounter self-driving vehicles, which stop to let them pass. One of the area’s employers makes robots that make other robots. Students who learn robotics and other high-tech manufacturing skills in high school will have no problem finding a good job.

But as Tesla’s executives probed further into its high-performers’ experiences with the clubs, they found something else. The clubs’ competitive aspect teaches students to solve problems on the fly. They’re fun for kids of any age and draw a diverse array of participants, including girls. Students compete, but they work together to do so.

Accordingly, one of the things Tesla has funded is a robotics coordinator for Washoe schools.

In 2019, students at Reed High School won a $10,000 grant from the Lemelson-MIT Program, which rewards student inventors. Their proposal: use a 3D printer to create a flywheel that would extract cigarette butts from storm sewers, preventing toxins within from poisoning fish in a nearby lake.

The senior who conceived of the idea went to the school’s energy technology classes to recruit volunteers. Many of those who joined the effort had participated in robotics clubs since middle school. The students used the grant money to test and refine the idea.

“Once you identify that thread and start pulling on it, it’s like, ‘Oh, of course, this makes sense,” says Fleming. “It’s that engineer’s curiosity.” Students taught to continuously test and refine their creations, whether an invention or a process, she points out, are going to drive the innovations that will shape the economy in the years to come — and in the process, secure jobs that will place them firmly at the top of the K.

Reno’s success in reinventing itself as a high-tech hub and attracting associated growing industries is great, she says. But looking further out, the key to true long-term economic health is whether regional officials — and the school system — can nourish Reno’s blossoming startup sector. The same problem-solving and collaboration skills that make robotics club participants prized members of Tesla’s current workforce, Fleming says, will make today’s high school graduates the entrepreneurs whose innovations will keep the local economy nimble.

“Northern Nevada has made progress transitioning from service to production,” says Fleming. “As your community transitions from production to a knowledge-based economy, that’s crucial.”

This article is part of a series examining COVID’s K-shaped recession and what it means for America’s schools. Read the full series here.

Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Chan Zuckerberg Initiative provide financial support to Opportunity Insights and The 74.

Lead images: Getty Images

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!