The Growing College-Degree Wealth Gap

A new report demonstrates a stubborn chasm between rich and poor students earning bachelor’s degrees.

The nation’s colleges continue to graduate far fewer students who grew up in poor households. With the country’s economic potential possibly hanging in the balance, a new report urges the United States to dedicate more resources and know-how to closing the college-completion gap between wealthier students and those from low-income backgrounds.

The issue boils down to the number of college-educated workers that will be needed to fill the bulk of the country’s new jobs—two-thirds of which will require some college background by 2020—and the dearth of college degrees held by lower-income workers. With well-paying jobs in manufacturing and the trades largely a relic of the nation’s industrial past, the middle-class pathways for workers with just a high-school education are few and far between. The basic arithmetic underscoring America’s labor needs points to a possible future in which the poor are unable to take full part in the nation’s economy, creating great social and economic strain.

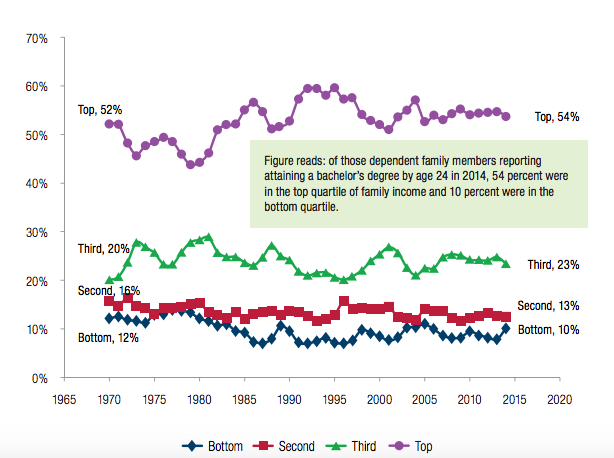

Among the report’s findings: When American households are organized into four income groups, 24-year-olds from the top two groups accounted for 77 percent of the bachelor’s degrees awarded in 2014. In 1970, that figure was 72 percent, suggesting that growing up in a wealthier household matters even more now in completing a degree than it did four decades ago. Graduates who hailed from households with incomes of at least $116,000—the top quarter—represented more than half of all the degrees awarded in 2014 among 24-year-olds. Students from households that earned less than $35,000—the lowest quarter—represented just 10 percent of all the degrees awarded. The report, which relied on U.S. Census and other data sources, was released by scholars at the University of Pennsylvania, Council for Opportunity in Education, and the Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education.

The findings represent a revision of data published last year in a similar report that was called into question by other scholars.

The Distribution of Family Income for 18-to-24-Year-Olds Who Earned a Bachelor’s Degree

A different collection of datasets the researchers used shows that 60 percent of students from the top quarter of households by socioeconomics graduate with bachelor’s degrees within 10 years of finishing high school—four times as often as students from the lowest quarter of households.

The colleges students attend vary significantly according to family wealth, as well. Nearly 70 percent of students in the nation’s most selective colleges are from that top socioeconomic quartile; the same is true for just 4 percent of students from the lowest socioeconomic rung, according to federal surveys of 2002 sophomores that the researchers used. (One major bone scholars have to pick with federal college data is that clear information linking family wealth to degree completion is hard to come by, and the information that is available is often outdated.)

Students eligible to receive federal grants because they were considered low-income were more than three times as likely to attend for-profit institutions in 2013 as students who didn’t receive federal grants. For-profit colleges typically charge higher tuition rates than four-year and two-year public schools and generally have far lower graduation rates than public four-year schools.

“Differences in enrollment patterns by family income reflect the stratification of the financial, academic, and other resources that are required to enroll in different colleges and universities,” Laura Perna and Roman Ruiz of the University of Pennsylvania and a colleague wrote in an essay accompanying the report. “Students from higher-income families have the resources that enable meaningful choice from among the array of available options nationwide. But, resource constraints and structural failures often limit the ‘choices’ of students from lower-income families to the local or online, non-selective or for-profit postsecondary educational institution.”

Many advocates argue that changing the federal financial-aid system to increase the amount students can receive in grants rather than loans with favorable interest rates would ease the concerns of high-performing, low-income students about college affordability. To that end, one proposal in the report calls for increasing the maximum Pell grant award—the primary federal higher-education grant aid for low-income students that today maxes out at around $5,800 per academic year—to $13,000 per student. States, the report goes on to propose, would cover half of that new $13,000 Pell award. “If states had invested in public higher education in 2015 at the same rate they had in 1980 they would have appropriated $65.2 billion more than they did,” according to the report.

Another suggestion? Federal programs designed for low-income college-bound students, like GEAR UP and Upward Bound, should be expanded. The report tallies that only 10 percent of eligible students are able to take advantage of these programs, which have been shown to vastly increase the odds of these students either entering or graduating from four-year colleges and universities.

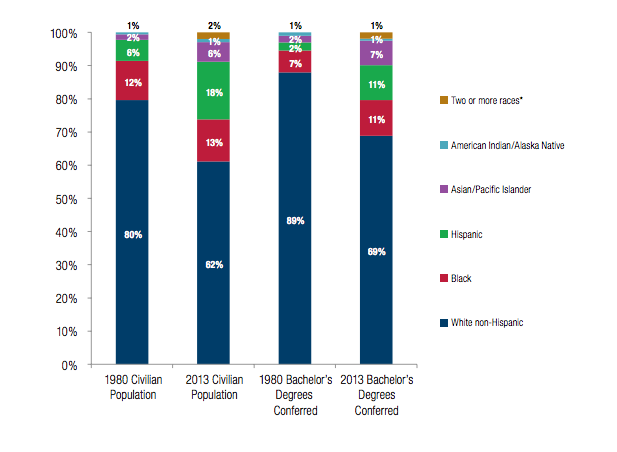

While the data presented in the report demonstrate a stubborn chasm between rich and poor students earning bachelor’s degrees, there has been notable progress in the college-going and completing rates for students at the racial group levels.

Between 1970 and 2014, the percentage of high-school graduates who went on to college increased from 49 percent to 68 percent for whites, 45 percent to 71 percent for blacks, and 53 percent to 65 percent for Hispanics. Data for Asian Americans is only available from 2000 and onward; in 2014, 86 percent of Asian American high-school graduates advanced to college. Still, black and Hispanic students historically have had higher high-school dropout rates than white and Asian American students.

The chart below captures degree completion data by race.

College-Degree Completion by Race

This article appears courtesy of the Education Writers Association.