The Struggle of Work-School Balance

In colleges around the country, most students are also workers.

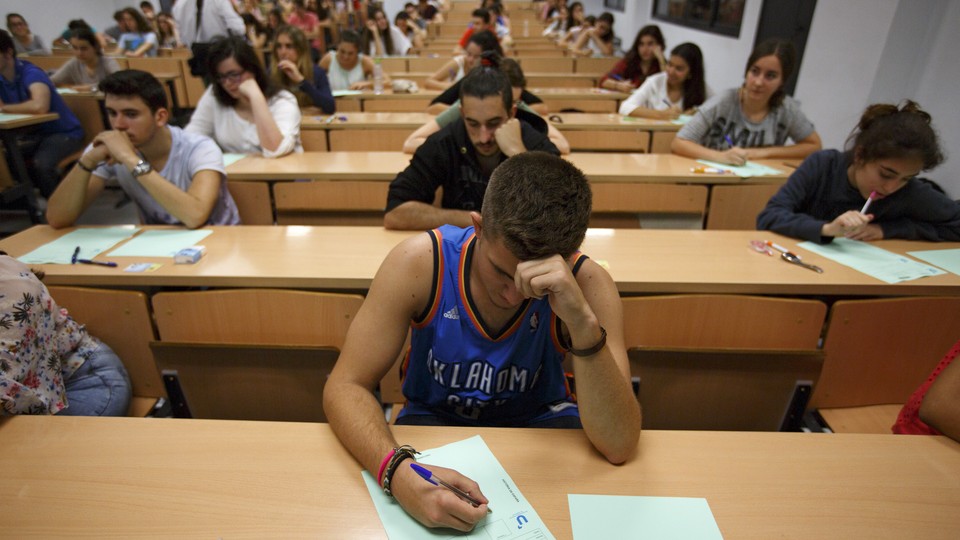

The reality of college can be pretty different from the images portrayed in movies and television. Instead of co-eds who wake up late, party all the time, leisurely toss footballs around, and intermittently study for exams, many colleges are full of students with pressing schedules of not just classes and activities, but real jobs, too.

New research from Anthony P. Carnevale, Nicole Smith, Michelle Melton, and Eric W. Price of Georgetown University, finds that this is the norm, with nearly 14 million Americans working while taking classes. They make up about 70 to 80 percent of college students, and nearly 10 percent of the overall labor force.

This isn’t a temporary phenomenon, the share of working students has been on the rise since the 1970s, and one-fifth of students work year-round. About one-quarter of those who work while attending school have both a full course-load and a full-time job. The arrangement can help defray tuition and living costs, obviously. And there’s value in it beyond the direct compensation: Such jobs can also be critical for developing important professional and social skills that make it easier to land a job after graduation. With many employers looking for students with already-developed skill sets, on-the-job training while in college can be the best way to ensure a gig later on. And with the rising cost of tuition and declining share of summer jobs going to young adults, working throughout the year can be a necessity in order to make college possible at all.

But it’s not all upside. Even full-time work may not completely cover the cost of tuition and living expenses. The study notes that if a student worked a full-time job at the federal minimum wage, they would earn just over $15,000 each year, certainly not enough to to pay for tuition, room, and board at many colleges without some serious financial aid. That means that though they’re sacrificing time away from the classroom, many working students will still graduate with at least some student-loan debt. And working full-time can shrink the chance that students will graduate at all, by cutting into the time available for studying and attending classes.

What’s troubling is that those who tend to struggle under the weight of difficult work and educational burdens are often those who have few other options when it comes to financing their education. They’re disproportionately older students who are black or Hispanic and low-income. This group is more likely to work out of necessity and to attend community colleges where resources—like career counseling—are scarce. They’re less likely to have access to outside financial and social resources to assist them in paying for school or finding a job afterward. They’re also less likely to finish school at all.

The labor-market reward for attending but not finishing college is marginal at best. That means that students who wind up leaving school because of difficulty managing work and class are likely to find themselves stuck in some of the same jobs they might’ve gotten if they hadn’t gone at all. And if they took out loans, they’re in worse shape all told. The difficulty of working too much while in school can create a cycle that pushes students further into debt without receiving any of the financial or career benefits promised by the pursuit of higher education.