By Jeff Strohl, Director

As a parent, I worry about my child’s future. Soon after a recent trip to pick up my son following his first year of college, I encountered several other parents with similar concerns: our taxi driver worrying that his son is facing slowdowns in computer science hiring; my colleague wondering how long her daughter will be living at home after graduation; another parent preparing for the first year to end, commiserating that our children are fortunate to be near the start of college rather than graduating in times of such uncertainty. In each of these conversations, tension lay just beneath the surface. All of us were wondering: What does the future hold post-graduation?

Recent media reports on the plight of the recent college graduate add fuel to these fears. The stories are bleak: More and more people say “college isn’t worth it,” AI is replacing recent and future college graduates, and job seekers are submitting countless applications but gaining few interviews. A great army of the newly unemployed, including casualties of DOGE-related reductions in force, raises the specter of recession—Washington, DC, is already feeling the effects, but the layoffs reach far and wide. And with the latest cycle of college graduations, we can expect a spike in similar stories on high unemployment rates and slowing job prospects for recent college graduates.

Many believe that these trends could signal the death knell for American higher education. And there is no denying that recent college graduates with a bachelor’s degree face mounting problems. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), last fall, unemployment for recent bachelor’s degree recipients was higher than that for recent associate’s degree recipients. If the trend holds this spring, it could defy the longstanding argument that a four-year college degree provides additional protection during hard economic times.

I don’t want to diminish anyone’s concerns about these trends. But I do want to underscore that the crystal ball is blurry when it comes to predicting longer-term outcomes for today’s graduates, and context is important when interpreting the data. It’s very difficult to project the labor-market impact of new technologies like AI and sweeping policy changes like tariffs. We do know, however, that today’s trends may be affected by three important factors:

- Every graduation cycle creates a spike in the supply of workers that the economy needs time to absorb.

- It takes time for recent college graduates to find a career pathway, but unemployment declines quickly once they do.

- Workers with higher levels of education have lower levels of unemployment.

First, regarding the supply spike: Millions of graduates hit the market each year in what we have called the “summer surge.” For the 2024–25 academic year, the National Center for Education Statistics projects that roughly 1 million associate’s degrees, 2.2 million bachelor’s degrees, and 1.1 million master’s and doctoral degrees will be conferred. Even under the best of circumstances, it takes time for the economy to absorb so many workers (our research indicated more than a year). At the same time, this year’s college graduates may have a rockier landing than usual. The Job Outlook 2025 Spring Update published by the National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE) indicates that hiring expectations for the class of 2025 are worse than they were last fall, and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s recent first-quarter release on “The Labor Market for Recent College Graduates” shows that the unemployment rate for recent college graduates jumped from 4.6 percent in March 2024 to 5.8 percent in March 2025.

Second, regarding the time required for graduates to settle into career pathways: The BLS analysis shows higher unemployment for recently graduated bachelor’s degree holders than for recently graduated associate’s degree holders in their year of graduation. In contrast, data on young workers who have had time to settle into the labor market tell a different story. These longer-term data show lower unemployment rates for young workers with a bachelor’s degree than for young workers with an associate’s degree. These data also demonstrate that all new labor-market entrants, not just college graduates, are sensitive to business-cycle effects, with unemployment spikes at all levels of educational attainment in 2002 (post 9/11), in 2009–11 (during the Great Recession), and in 2021 (post COVID-19) (Table 1).

Table 1. With time to settle into the labor market, bachelor’s degree holders have lower unemployment rates than associate’s degree holders, and both have lower unemployment rates than workers without a postsecondary degree.

| Unemployment rates | ||||

| High school diploma (ages 18–24) |

Some college, no degree (ages 20–26) |

Associate’s degree (ages 20–26) |

Bachelor’s degree (ages 23–29) |

|

| 2000 | 11.2% | 5.4% | 3.3% | 2.1% |

| 2001 | 10.4% | 6.6% | 3.0% | 2.8% |

| 2002 | 14.1% | 8.4% | 7.8% | 4.0% |

| 2003 | 13.6% | 8.4% | 6.8% | 3.6% |

| 2004 | 14.1% | 9.6% | 4.8% | 4.1% |

| 2005 | 13.4% | 7.6% | 6.0% | 3.6% |

| 2006 | 11.7% | 6.7% | 5.5% | 3.0% |

| 2007 | 10.5% | 6.9% | 5.6% | 2.8% |

| 2008 | 13.7% | 6.7% | 5.4% | 2.8% |

| 2009 | 22.0% | 12.2% | 8.5% | 5.7% |

| 2010 | 23.7% | 14.3% | 9.6% | 5.5% |

| 2011 | 22.8% | 13.2% | 10.1% | 5.7% |

| 2012 | 20.1% | 13.6% | 8.4% | 5.0% |

| 2013 | 19.6% | 11.9% | 8.6% | 5.0% |

| 2014 | 18.9% | 11.5% | 4.3% | 3.4% |

| 2015 | 17.1% | 10.0% | 6.1% | 3.1% |

| 2016 | 13.8% | 9.5% | 7.8% | 3.2% |

| 2017 | 10.4% | 6.9% | 5.2% | 3.7% |

| 2018 | 12.2% | 5.9% | 4.9% | 2.7% |

| 2019 | 9.9% | 7.5% | 4.3% | 2.6% |

| 2020 | 13.6% | 8.3% | 5.5% | 4.3% |

| 2021 | 14.0% | 12.0% | 8.4% | 5.6% |

| 2022 | 10.6% | 9.4% | 5.1% | 3.7% |

| 2023 | 9.3% | 5.8% | 4.3% | 3.5% |

| 2024 | 10.1% | 6.3% | 5.9% | 4.1% |

Source: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce analysis of data from the Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement, 2022–24 (pooled).

Note: The figure shows moving averages for three years of age.

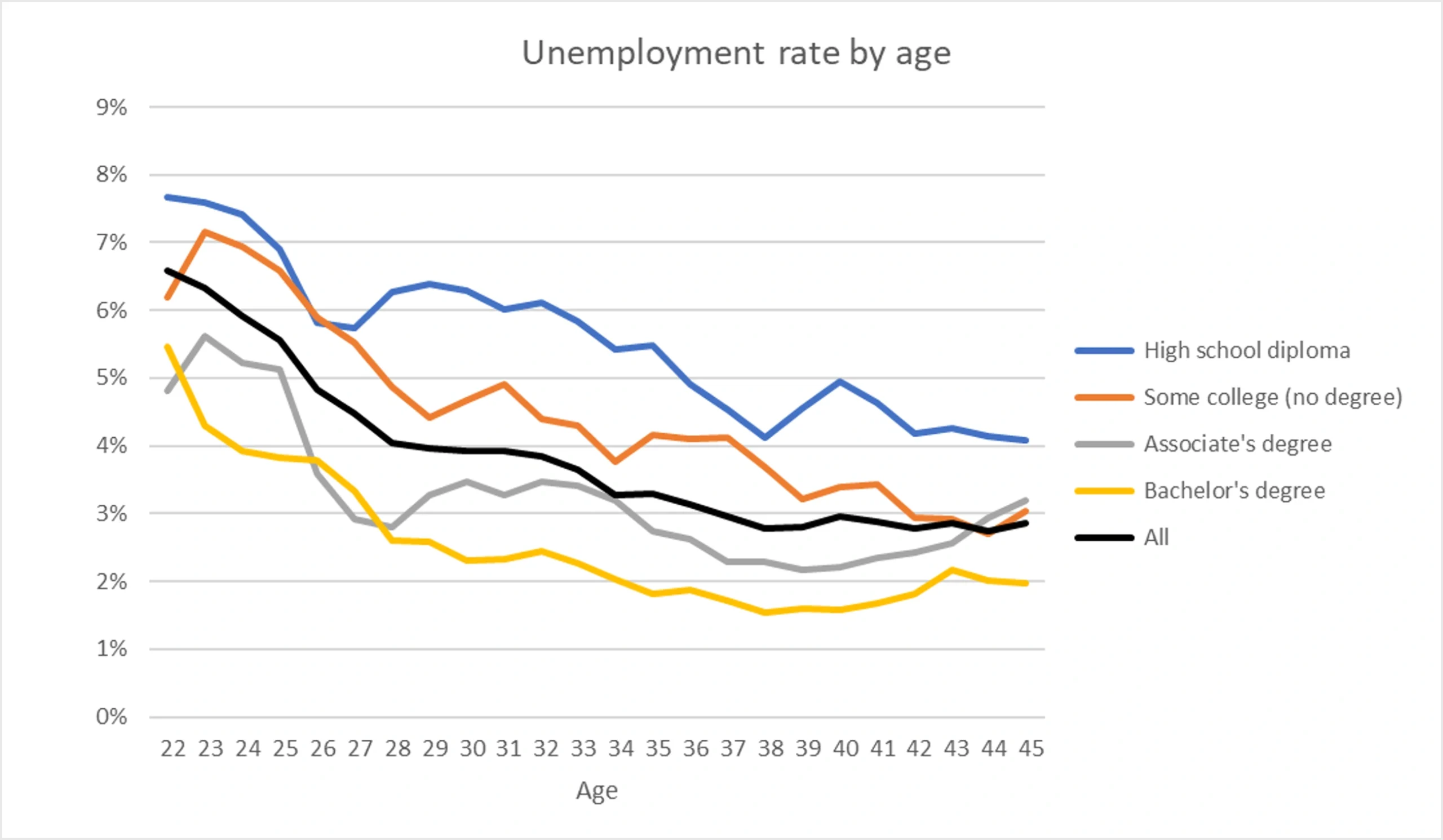

Finally, comparing unemployment rates among workers of the same age confirms that a college degree—and especially a bachelor’s degree—provides protection against unemployment in the long run. Our analysis shows that unemployment is sometimes higher among bachelor’s degree holders than among associate’s degree holders when workers are in their mid-twenties (Figure 1). But by the time workers are in their early thirties, bachelor’s degree holders firmly hold the advantage, maintaining the lowest levels of unemployment among workers at all educational attainment levels into at least their forties.

Figure 1. By their late twenties, workers with a bachelor’s degree have the lowest unemployment rates of all educational attainment groups.

So, what does all this mean for the class of 2025? There’s one thing we can say with certainty: The employment prospects for recent college graduates are worse than they were last year. But as we navigate another graduation season full of news reports that amplify the plight of the recent college graduate, keep in mind that the dynamics of our labor market depend on long-term and cyclical trends. The temporary excess supply of recent graduates always raises unemployment rates temporarily, and even the effects of longer-term shocks to the economy will subside with time. Our research has shown time and again that the bachelor’s degree is an investment that pays off in the long run. And while we shouldn’t be etching a tombstone for the college degree, we should be focused on smoothing the transition between college and careers. We owe it to our children and their futures.